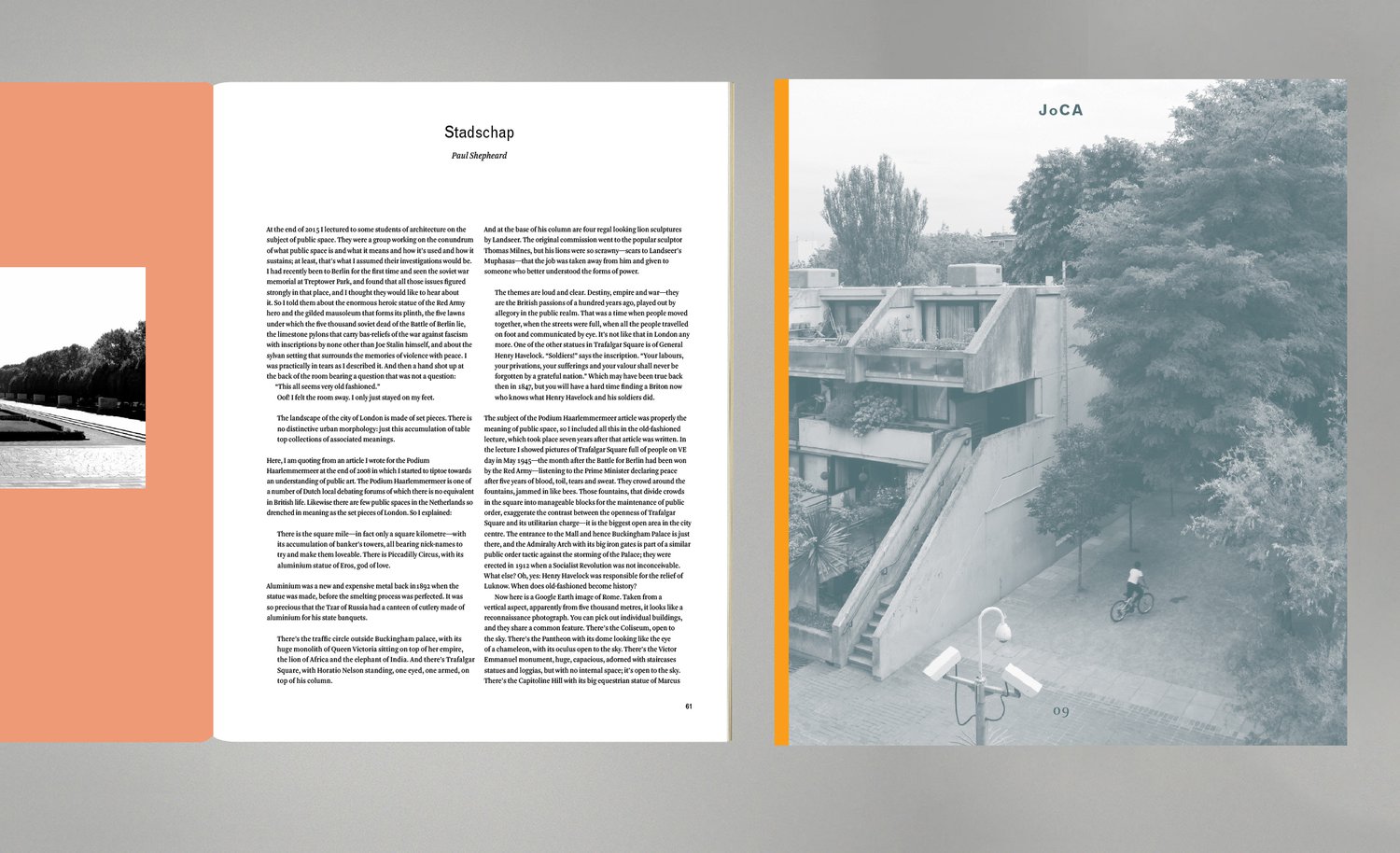

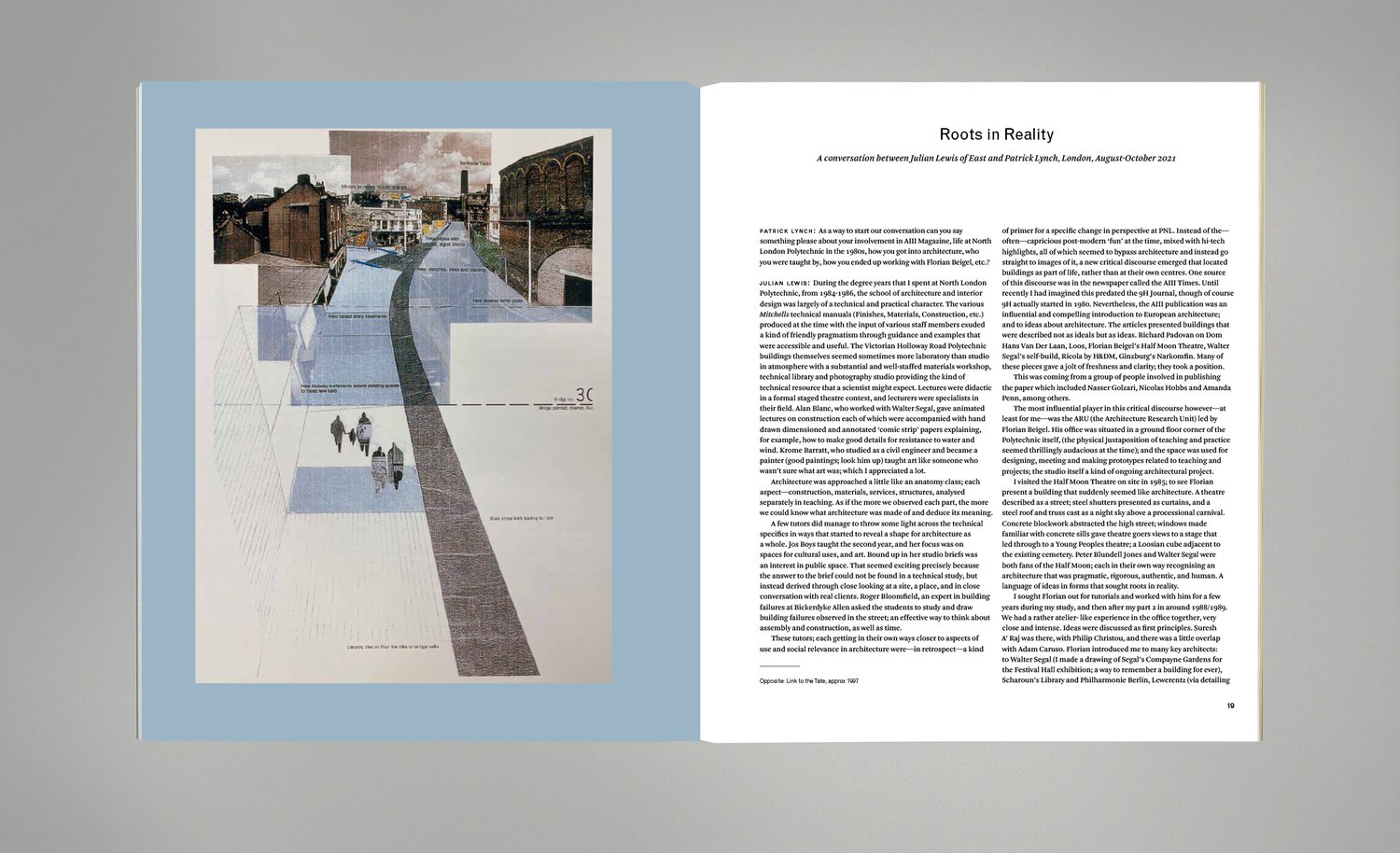

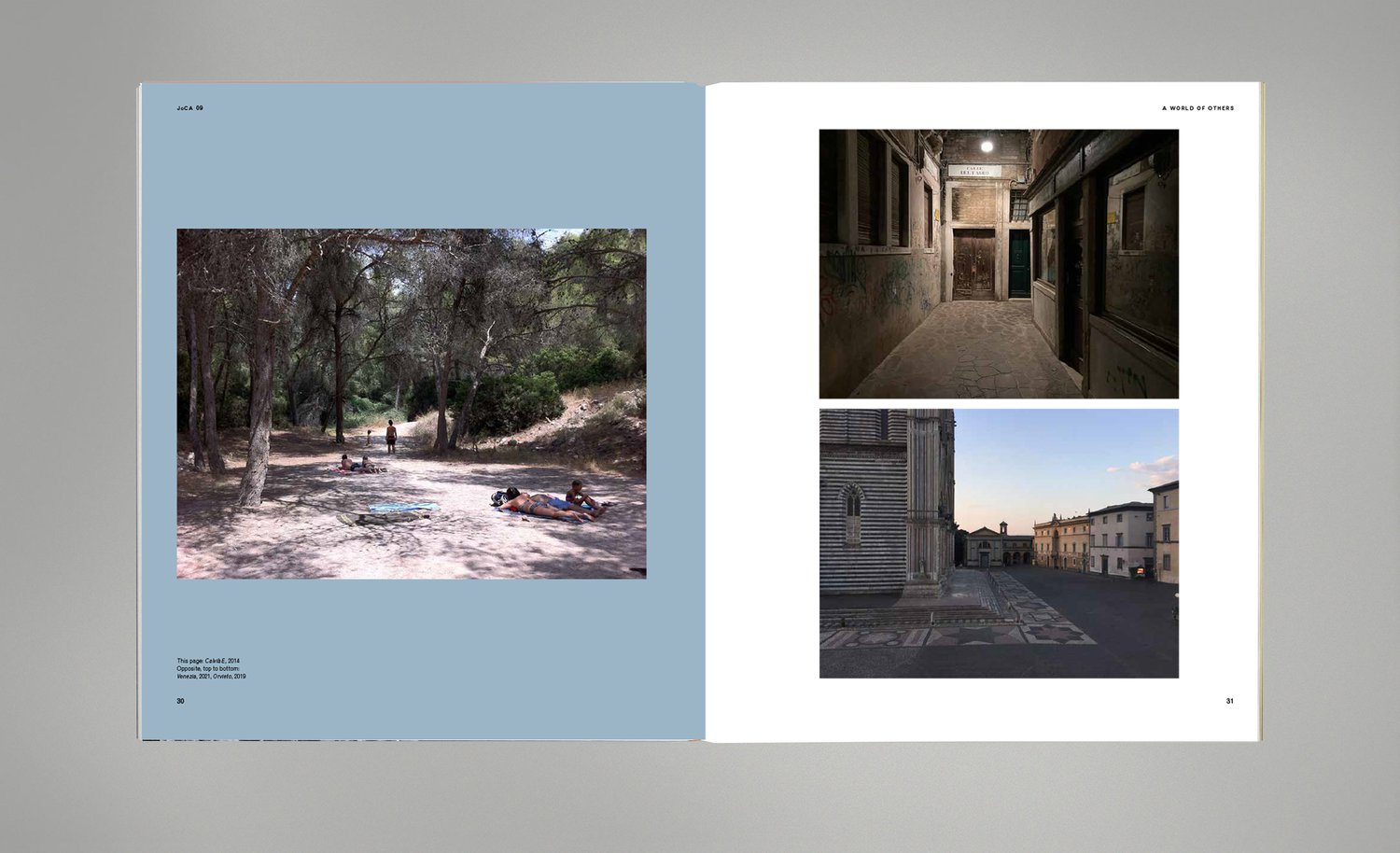

The Journal of Civic Architecture (JoCA) includes essays, visual essays, drawings and design projects that relate architecture, photography, literature and criticism to city life. Each issue is edited by Patrick Lynch, and addresses a series of unpredictable themes concerning urban culture and imagination.

Contributions are invited for the forthcoming issues from photographers, writers and designers who wish to engage in a fruitful dialogue with other creative people about the meaning, frustrations and pleasures of civic culture today. Academics are encouraged to send things that perhaps wouldn’t otherwise find an audience. Please contact us if you’ve design projects, writing, or images that you’d like us to consider for publication.

Each issue of JoCA has a limited print run of 500 copies, and is available to purchase from our website, Magma, magCulture, Rare Mags, Margaret Howell, Charlotte Street News, The Architectural Association Bookshop in London; and at CCA in Montreal, Copyright Books in Ghent, and at Choisi Bookshop in Lugano, Inga Books Chicago, amongst others.